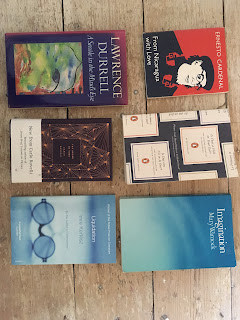

Book reviews 2018 - #15 through #20

#15 - “Imagination”,

Mary Warnock, 1976

Pretty heavy

duty philosophy, but with Warnock’s distinctive twists: art, culture and

psychology all make an appearance. It’s

mainly a historical review rather than a standalone argument, with Hume, Kant,

Coleridge, Wordsworth, Sartre and Wittgenstein as the main characters.

Key take out

is the importance of imagination to the human condition. Imagination is not ‘pretend’ or even

‘creativity’: integrated with perception, feeling and rationality, it lies at

the heart of who we are and how we behave.

There. You don’t need to read it now.

#16 - “A

Smile in the Mind’s Eye”, Lawrence Durrell, 1980

A

curio. Part essay on the nature of the

tao, part philosophical stroll, part memoir, this short book is probably of

interest only to people who have read a great deal of Lawrence Durrell and want

to fill in the gaps. If you want to know

about the tao, or to explore related philosophy, this probably isn’t the best

place to start.

It was also

written towards the end of Durrell’s life and to me he feels tired. I read it and just felt a bit sad.

#17 - “Liquidation”,

Imre Kertesz, 2003 (trans. Tim Wilkinson)

Kertesz was

born in Hungary in 1929. He was

imprisoned in both Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2002.

Liquidation

is the second of his books I’ve read; the first was ‘Fiasco’. Neither was an easy read, in terms of both style

and content. Style-wise, we’re talking

elliptical, strange, uncanny, with nested, looping perspectives and

clever-bastard architecture.

Content-wise we’re talking ‘the human condition’ - especially human

frailty – the difficulties of authentic communication and, of course, the

Holocaust.

This is

powerful, important literature and I loved it.

His work feels to me to be in the same space as Samuel Beckett, W G Sebald and Iain Sinclair. Sometimes you

get to the end of a paragraph and have no idea what just happened, but you feel something, and you know it’s big,

important. You can only let it settle

inside you and do its work.

#18 - “The

Order of Time”, Carlo Rovelli, 2017 (trans. Simon Carnell and Erica Segre)

Right. This is a tricky one.

On the one

hand, this comes out of the Adelphi stable, which is the Italian publishing

house overseen by Roberto Calasso. As

you know, Calasso is a genius of whom I am in awe, so the provenance is strong.

In addition,

my dear friend Robin recommended this to me after seeing Rovelli in the flesh

and having pronounced him to be a genuinely wonderful chap. Rovelli is a theoretical physicist with the

rare gift of being able to speak human.

Given the staggering importance of theoretical physics, and the

implications of contemporary science for the future of humanity, I’m obviously

hugely in favour of anyone and anything that can explain it to us.

On top of

all that, this is a book about the nature of time – granular, stranger than we

can possibly imagine, almost not the thing we think of as ‘time’ at all – which

is definitely my kind of reading material.

On the other

hand – this guy really gets on my tits.

There’s just something about him that annoys the hell out of me. His style, possibly? His metaphors and similes are systematically

weak. He leaps from impressive

expositions of incredibly complex physics to trite homilies on the human

condition in a single bound. He tries to

formulate a crypto-religious redemption in the face of the blistering reality

his science is exposing and – to my mind – just feels naïve. Some of the things he presents as profound

insights are things I wrote down aged 22 and look back on now as preliminary.

Still, loads

of people seem to think he’s fabulous, and his previous book ‘Seven Brief

Lessons on Physics’ (which I also hated) has sold squillions of copies, so I

guess it must be me.

#19 - “Is

that a fish in your ear?”, David Bellos, 2011

This is a

truly marvellous book that you should read immediately. Bellos is a multi-award winning translator

whose work I first encountered many years ago, though I didn’t realise at the

time because I thought I was reading a book by Georges Perec. Well, I was

reading a book by Georges Perec, but the only reason I was able to read a book

by Georges Perec was because someone had gone to the trouble of translating

Perec’s words from French into English.

And that

someone – to whom I am incandescently grateful, given the joy I derive from

reading Perec – is David Bellos. (I have

emailed him to tell him so.)

“Is that a

fish in your ear?” has the sub-title ‘The amazing adventure of translation’ and

it is, in large part, the story of what translation is, and how it works, and

how it doesn’t when it doesn’t. It turns

out that what we call ‘translation’ is merely one part of the more general

process by which meaning is communicated between sentient beings, which means

that a story of ‘translation’ morphs into an extended and beautiful riff on the

nature of meaning, on the power of story, on the perils of communication and

even what it means to be a human being.

(What is a human being, after all, if not a story-based animal that

communicates meaning with other animals?)

Bellos writes with the assurance and authority that comes from being

totally at ease with what he is doing; and both his argument and his

illustrations are utterly engrossing.

I’m biased,

of course, because I’m such a fan of Perec.

There are two or three places in the Bellos book where he references the

kinds of literary or linguistic games that Perec would play. Bellos talks about the meta-game of turning a

game in one language into a game in another, where the nature of the game may

itself be a game that can only be played in one language. Acrostics, for example, embedded as clues in

a French detective story - a story that is itself based on clues embedded in an

unfinished story – can only be translated into English with extraordinary

skill, flair and creativity. Bellos has

these things in abundance. Reading him

was a privilege.

#20 - “From

Nicaragua with Love”, Ernesto Cardenal, 1986 (trans. Jonathan Cohen)

This is CityLights’ Pocket Poets #43. I’ve been

collecting the Pocket Poets for 30-odd years now. The rule is: no cheating. No internet.

No google. No asking the

bookseller to find something for you.

The book must find you.

This one

found me in Skoob, under the Brunswick Centre.

According to the cover:

“The liberation theology of this impassioned

poet-priest is inherent in his poetry as it is in his public life, for these

poems articulate his hope for a “society of love” in Nicaragua, which is what

the revolution means to him.”

It’s long

intrigued me, this South American thing, where the boundary between politics

and poetry is so blurred.

In this

case, the poetry isn’t actually very good: but that doesn’t really matter. How often do you encounter a poem like this?:

ECONOMIC

BRIEF

I’m

surprised that I now read

with great interest

things like

the cotton harvest up 25%

from last

year’s crop

U.S $124.2 million worth of coffee exported

up 17.5% from last year

a 13.6% jump

in sugar is expected

corn production dropped 5.9%

gold dropped 10% because

of attacks

on the contras in that region

likewise

shellfish…

When did

these facts ever interest me before?

It’s because now our wealth

meagre as it may be

is intended

for everyone.

This interest of mine

is for the people, well,

out of love

for the people. The thing is

now these

numbers amount to love.

The gold

coming out of the earth, solid sun

cut into

blocks, will become electric light,

drinking

water,

for the poor. The translucent

molluscs,

recalling to mind women, the smell of a woman

coming out

of the sea, from their underwater caves

and

colourful coral gardens, in order to become

pills,

school desks.

The holiness of matter.

Momma, you know the value of a glass of milk.

The cotton,

soft bit of clouds,

-

we’ve gone to pick cotton singing

we’ve held clouds in our fingers –

will become

tin roofs, highways and

the thing is

now what’s economic is poetic,

or rather, with the Revolution

the economy

amounts to love.

Wonderful.

Comments